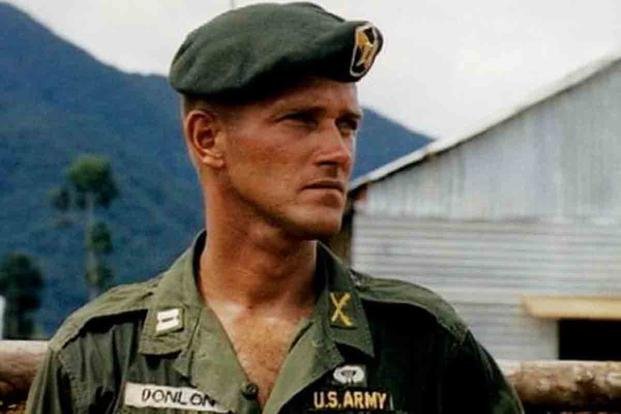

When Roger H.C. Donlon joined the Army in 1958, he was already familiar with military life. He had enlisted in the Air Force in 1953, but left to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York. In 1957, he resigned from the academy to just get into the Army — and maybe meet his destiny, if you believe in that sort of thing.

After Officer Candidate School, he qualified for Special Forces. He was sent to Vietnam in 1964, where he would receive the Medal of Honor for his courageous and nearly fatal defense of an American training camp in July of that year.

Donlon died on Jan. 25, 2024, just five days before his 90th birthday.

In the early morning hours of July 6, 1964, then-Capt. Roger Donlon was about to wake up the next guard for duty when a white phosphorus round came hurtling through the hut’s thatched roof, lighting it on fire. The training camp at Nam Dong was already surrounded by the time the Americans scrambled to their defensive positions. As the commander of the detachment, it was up to Donlon to mount the defense, and he had his work cut out for him.

“It was the first time the North Vietnamese Army came down and linked up with the Viet Cong guerrillas in the south to overrun an American Special Forces training center,” Donlon told the American Legion in 2016.

In 1964, the United States had a presence in South Vietnam, but hadn’t yet committed the tens of thousands of combat troops it would in the years to come. Americans were focused on equipping, advising and training the South Vietnamese, while U.S. Special Forces soldiers trained indigenous groups on conducting irregular warfare, a program called Civilian Irregular Defense Group, or CIDG.

It was at one of these CIDG indigenous training bases in Vietnam that Donlon would lead his Vietnamese trainees and their Australian and Special Forces advisers in a five-hour firefight so intense that American helicopters could not land to extract the wounded.

Donlon was on guard duty when 800 North Vietnamese troops blew the roof off their makeshift chow hall at 2:30 in the morning. Inside the camp were just 360 CIDG trainees, 12 Green Berets and one Australian adviser. As mortars rained down, he marshaled his men to move ammunition from the burning buildings and set up defensive lines. He then started moving ammo where it needed to go.

As he began running ammo to his gun crews, he saw the camp’s main gate was under attack by a team of Viet Cong sappers. To prevent them from breaching the outer perimeter, he stopped his ammo run to eliminate all three of the sappers. Then, through a hail of enemy grenades, he dashed for a mortar pit, taking a severe stomach wound as he moved. When he got to the pit, he found the gun crew there had also been wounded. He shoved a handkerchief into his stomach wound and covered its withdrawal.

As he dragged the team’s wounded sergeant out of the pit and to the next defensive position, Donlon was wounded again, this time by a mortar in his left shoulder. Despite these injuries, he had to keep moving. Through enemy fire, he carried a 60-millimeter mortar to a new location, where he found more wounded men, administered their first aid and armed them with the mortar and a 57-millimeter recoilless rifle he’d picked up from another gun pit. As he left to return with more ammunition for the weapons, he was wounded a third time, as a grenade sent shrapnel into his leg.

Now crawling, he directed mortar fire to the eastern sector of the camp. He would have to move from position to position for the rest of the battle, directing his men while lobbing grenades of his own. He was wounded a fourth time as a mortar peppered his face and body. When daylight came and helicopters were finally able to remove the wounded, about 60 enemy troops were dead, along with 57 South Vietnamese, two Americans and their one Australian adviser. He waited until every last one of his wounded soldiers were evacuated before he allowed himself to be taken.

Donlon was presented with the Medal of Honor by President Lyndon B. Johnson in a White House ceremony on Dec. 5, 1964. He was the first of 268 Medal of Honor recipients of the Vietnam War. He spent the rest of his 30-plus-year career in the Army, retiring as a colonel in 1988.

“I wear this award on behalf of those who didn’t come home,” he later said. “I’ve had many great opportunities to share their sacrifices.”

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you’re thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Story Continues

Please rate this CIBA article

Vote