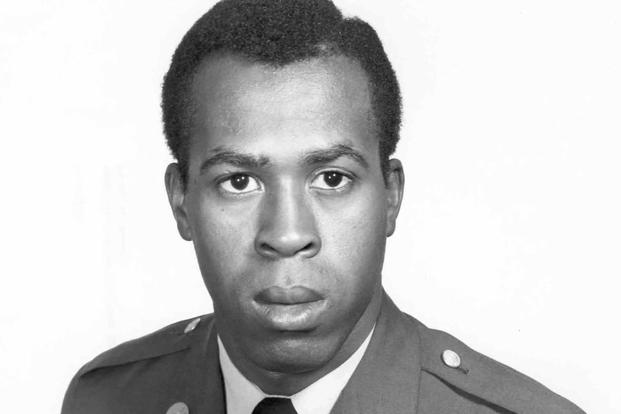

Clarence Sasser, one of the Vietnam War’s few remaining Medal of Honor recipients, died last week at the age of 76.

In 1968, while serving as a medic with the Army’s 3rd Battalion, 60th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division, Sasser’s company unexpectedly came under heavy enemy fire while making an aerial insert into a rice paddy in Vietnam’s Mekong River delta, amidst an effort to root out reported Viet Cong combatants in the area.

Sasser sustained a leg wound almost as soon as he exited his helicopter. Within the first few minutes of a dozen or so helicopters dropping off troops, his unit — around 115 soldiers in all — suffered more than 30 casualties.

Read Next: AI-Created Porn Targeted Taylor Swift. Now, Lawmakers Want to Make Sure That’s a Crime in the Military.

The then-private 1st class braved multiple hailstorms of bullets and rocket fire to tend to his teammates. Sasser would later leave the Army in 1969 as a specialist 5th class.

“Without hesitation, Spc. Sasser ran across an open rice paddy through a hail of fire to assist the wounded,” his Medal of Honor citation read. “After helping one man to safety, he was painfully wounded in the left shoulder by fragments of an exploding rocket.”

Sasser had been one of three living Black Medal of Honor recipients.

According to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, there are just 61 living Medal of Honor recipients. Of the more than 3,500 Medals of Honor bestowed on service members, Black veterans are historically significantly underrepresented.

No Black service members received the honor throughout World War I or II, which historians attribute to Jim Crow-era racism and a “culture of discrimination at the highest reaches of the War Department.” Most Black recipients received their awards decades later.

After returning to the U.S. from Vietnam, Sasser received his Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon in 1969, in a ceremony in which two other service members received the highest military honor, according to the Defense Department.

“Shell fragments are … something I’ll never forget how they feel,” Sasser said in 2001, recounting the wounds to his back as part of an interview with the Library of Congress.

“It’s almost no pain; the pain sets in later,” he said. “The initial shock is what you experience and the searing, of course, ’cause the shell fragments are hot.”

Sasser refused medical attention, running back again through heavy gunfire to aid more of his wounded comrades. Bullet wounds and watchful Viet Cong snipers prevented Sasser and his wounded teammates from running out of the kill zone — so Sasser told his teammates to crawl the length of almost two football fields, to a group of trees that would provide concealment.

“Despite two additional wounds immobilizing his legs, he dragged himself through the mud toward another soldier 100 meters away,” Sasser’s award citation continued. “Although in agonizing pain and faint from loss of blood, [Spc. 5th Class] Sasser reached the man, treated him, and proceeded on to encourage another group of soldiers to crawl 200 meters to relative safety.”

“If you stood up, you were dead,” Sasser said in his interview, adding that enemy snipers kept a special eye out for medics, to prevent aid from being rendered to wounded soldiers who might otherwise survive. “The best way to get around that day was just simply grabbing the rice sprouts and sliding yourself along.”

For the next five hours, Sasser tended to his teammates’ wounds until helicopters could arrive to evacuate the unit.

“I believed firmly that my job was to care for the guys,” Sasser continued in the 2001 interview. “I didn’t think that picking up a weapon would help [us]. My job was to treat ’em — to at least let ’em know that doc was around, and would come see if they called.”

Sasser said that he wouldn’t deny being afraid throughout the gunfight. “Of course you were afraid,” he said. “But these were my guys. … You were doc. You were afforded a place within their ranks.

“They looked out for you. Your job was to look out for them,” he said. “When they call — when they holler ‘medic’ or ‘doc’ — your job was to go. Nothing more. Without fear of your life or anything of that sort. It was your job.”

— Kelsey Baker is a graduate student at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, and a former active-duty Marine. Reach her on X at @KelsBBaker or bakerkelsey@protonmail.com.

Related: How the 3 Living Black Medal of Honor Recipients Embody the Military’s Top Award

Story Continues

Please rate this CIBA article

Vote